The Derna,

a cargo ship, departed from Turkey in September 1911. Its cargo hold was filled

with 20,000 rifles, 2 million rounds of ammunition and machineguns, destined to

the Ottoman-Libyan port of Tripoli and to be distributed amongst loyal Libyan

tribesmen. On 24 September, Italy caught wind of the ship’s journey and issued

a warning to the Ottomans that “sending war materials to Tripoli was an obvious

threat to the status quo” and endangered the Italian community in Libya. The

ship started unloading its cargo at Tripoli harbor on the 26th of

September. Infuriated, the Italian government issued a 24-hour ultimatum to the

Ottoman empire on the 28th: the regions of Tripolitania and Cyrenaica

are to fall under Italian jurisdiction and military occupation or else war

would be declared.

The Ottomans gave a reasonable and conciliatory reply but

Italy would have none of it. On the 29th of September, Italy

declared war on Ottoman Libya, a decision described by the Italian prime

minister Giovanni Giolitti as fulfilling una fatalia storica – a history

destiny.

|

| The Ottoman-Italian war (photo from Commons) |

Prelude

But why

Libya? At the time, Libya (formally called the vilayat of Tripolitania)

was a neglected region in the Ottoman empire. It had neither roads nor railways,

and produced (in the terms of a contemporary European writer) “products of

primitive husbandry” such as livestock and dates. The farming industry barely

managed to produce food to feed the whole population. What reasons did the

Italians have to be in Libya?

To answer

this question, we must go back to the time when Italy was born without Rome nor

Venice, in August 1863. The Opinione paper of Turin had warned that

“If Egypt and with it the Suez Canal falls to the British, and if Tunis falls to the French and if Austria expands into Albania, we will soon find ourselves without breathing space in the dead centre of the Mediterranean. “

|

| The Italian colonial empire, by 1940. |

Even

earlier, in 1838, Giuseppe Mazzini, who helped unify Italy, declared that North

Africa belongs to Italy. In the 19th century, Italy was a relatively

new & poor country that was seemingly surrounded by Great Powers on all

three sides; the French, the Austrian Empire, the Ottomans and the British.

Determined to become a Great Power in her own right, in the 1860s and 1870s,

Italy began to court Tunisia, Rome’s first African colony and then still an

Ottoman province. With a large Italian population of 25,000 by 1881, it seemed

that Tunisia would be easy-picking for Italy. Unfortunately, the Bey (governor)

of Tunisia accepted French rule in May 1881, dealing a blow to Italian pride

and sending the country’s politicians panicking.

France’s

interference in Tunisia inadvertedly lead to Italy entering the Scramble For

Africa, acquiring the unpromising but strategic regions of Somalia and Eritrea

in 1889. Italy soon set its eyes on Ottoman Libya, compensation in their view

for Tunisia. Control of Libya provided strategic access over the central

Mediterranean, and territory close to the lucrative Suez Canal trade. In

Italy’s view, they had to claim Libya to counter French (or others) influence

in the Mediterranean. Mussolini later commented,

“For others, the Mediterranean is just a route. For us, it is life itself.”

From the

1880s until 1911, Italy pursued a vague policy of “peaceful penetration”;

establishing Italian schools, encouraging the migration of Italian farmers in

Cyrenaica (eastern Libya), setting up of Italian banks and funding mineral

prospecting expeditions. The Italian public was largely supportive of the

movement; as far back as 1889, Italian nationalists, industrialists and the

Catholic Church had called for the colonial expansion, arguing that it would

combat Italy’s alleged overpopulation and mass emigration to the United States.

“To emigrate is servile,' Italians were told, 'but to conquer colonies is a worthy task for a free and noble people”

Nationalist newspapers depicted Libya as a

good source of grains and olives as well as possessing lucrative trade

routes. Italian explorers ventured to

Libya, calling it Italy’s Fourth Shore, and described the potential

wealth of the unexploited countryside and the seemingly endless green fields of

Cyrenaica (in 1911, a writer went as far as to say that 1/4th of the

country could be cultivated using irrigation).

But why not

simply invade? Why go through this decades-long process? The reason was that

the Italians feared an invasion of Ottoman Libya would result in a greater

European war, with perhaps the Austrians making unacceptable gains in the

Balkans, and potential backlash with France or other European powers. As a

result, the Italian diplomatic goal was to secure assurances and guarantees

from Europe’s powers. In the 1900s, Italy acquired assurances from Britain,

Austria & Germany (both being Allies), Russia and the United States. Year

after year, the Italians waited for their opportunity to strike. In 1911, in

the aftermath of the Agadiz crisis that saw France gain even more territory in

North Africa, Italy decided to act, scheduling an invasion in the autumn, when

the sea was calmest.

Italy needed

a casus belli and it found one. In 1908, two Italians (one of them a priest)

were murdered in Tripoli, and the Ottoman investigation proved inconclusive.

The Italian media hunched onto the story, claiming that Italian lives and

property were in danger in Libya and campaigned furiously for an occupation.

With the backing of the majority of the public (minus the Socialists, who

rioted against the idea of an “imperialist invasion”, interestingly enough

Mussolini was amongst the rioters and was jailed for his criticism of the

invasion) and the Catholic Church (who praised the “crusading spirits” of the

masses) , the invasion seemed in place.

War & Peace:

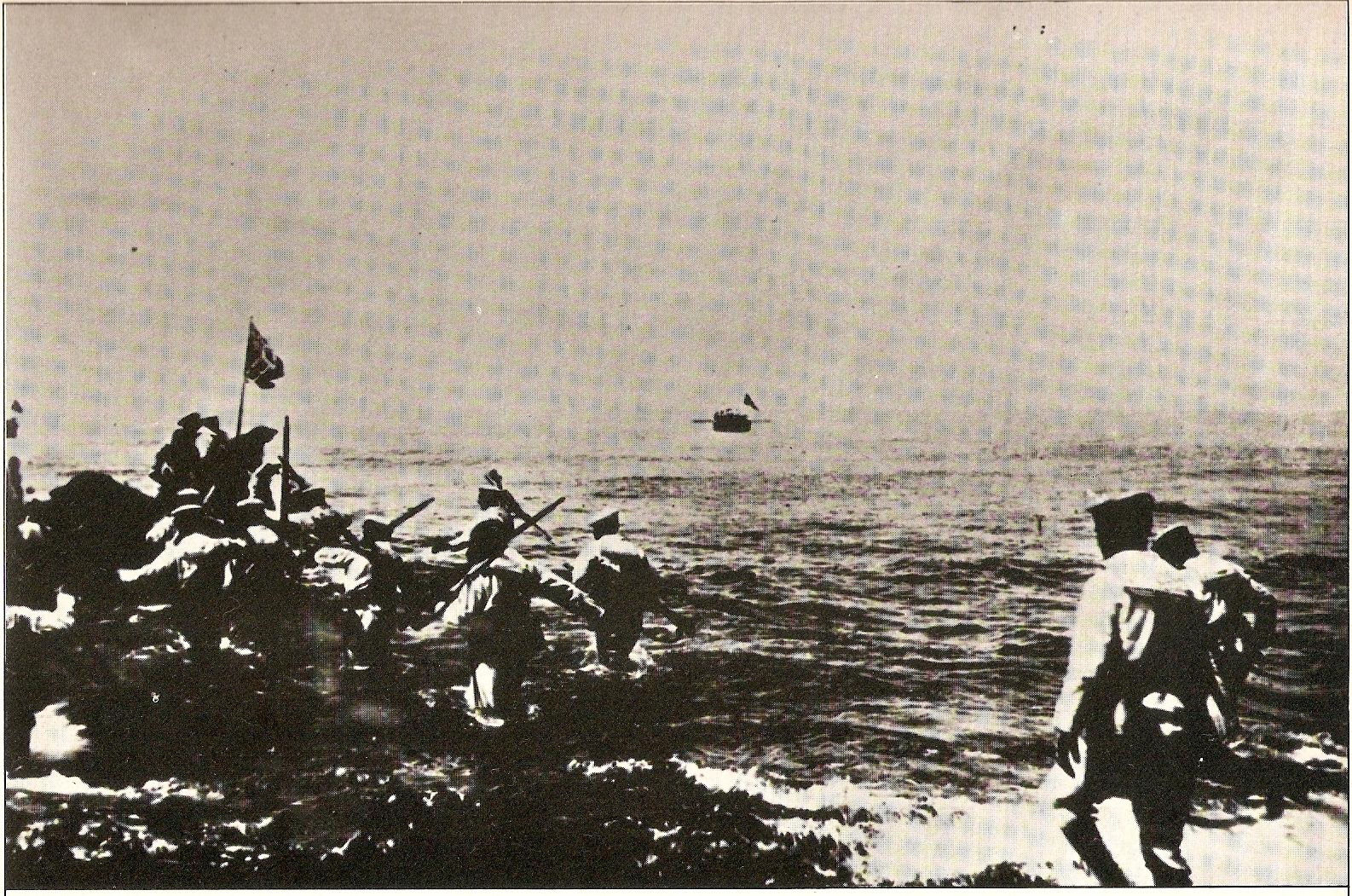

|

| Italian landing at Tripoli, October 1911 |

After the Derna

incident, four Italian battleships disembarked from Italy on the 1st

of October and anchored the next day outside of Tripoli. It was only at 3:15pm

on the 3rd of October that the ships began bombarding the three

Ottoman forts of Tripoli. On the 5th , 900 marines landed and

captured the badly-damaged forts. The Turkish commander and his depleted

garrison, seeking to spare the city from bombardment, withdrew from the city. By nightfall, around 1,700 more marines occupied the town of Tripoli. The

Ottoman garrison, numbering less than 5,000, regrouped with Libyan tribesmen

inland whilst the Italian vanguard awaited the arrival of the main

expeditionary force, which arrived a week later.

Italy had

hoped the Turks would seek negotiations after the capture of Tripoli but they

had no intention to. The Italians were surprised to face stiff resistance from

the native Libyans whom they thought would welcome them as liberators. East of

Tripoli, the Italians were almost overwhelmed by a combined Libyan-Turkish

assault at Henni on the 23rd of October. Meanwhile in Cyrenaica, Italian

amphibious landings and shelling resulted in the capture of Tobruk, Derna and

Homs on the 4th, 18th and 21st of October.

On

18 October, another Italian battle fleet (consisting of 7 battle cruisers and

20 transport ships) anchored outside Benghazi and issued a 24-hour ultimatum,

demanding the town’s surrender. The 280-man garrison defended the town against

hopeless odds. After the ultimatum expired, the fleet shelled the city to the

ground, destroying the city’s Grand Mosque and damaging the Franciscan mission

as well as the British and Italian consulates, all of which were packed with

refugees. Later that day, the Turkish garrison surrendered, but the Italian

occupiers faced unexpected resistance from the inhabitants of the suburbs. The

Turko-Libyan forces withdrew from the town in the next few days.

|

| Italian battery bombardment of Benghazi |

By the end

of October 1911, Italy controlled five beachheads on the Libyan coast and had

deployed 34,000 men, 6,300 horses, 1,050

wagons, 145 warships amongst others. The war was the first to see the deployment

of new technologies such as machineguns, radio-telegraph and motor-transport as

well as aeroplanes in battle.

The town of

Tripoli rioted against the Italians at the end of October but was brutally

suppressed. On 5 November 1911, the Italian King Victor Emmanuel issued a royal

decree, bringing Tripolitania and Cyrenaica under the Italian Crown. In what is

comparable to George Bush’s premature “Mission Accomplished” declaration in

2003, so too was King Victor’s. It would take twenty years before Libyan

resistance was effectively subdued.

The invasion

was a disaster primarily because it failed to account for the actions of the

native Libyan population. The Italians had hoped the Libyans would welcome them

as saviours from the corrupt Turks or at the very least to stay neutral in the

war. However, the Italians failed to recognize that the Libyans and the

Ottomans were bound in religion. Both people were Muslim and to the Libyans,

they were fighting against an invading Christian army akin to the Crusaders. This

blunder lead to the war being dragged out for a year, much to the relief of the

Turks who were also surprised by the support they were given.

Due to Italian naval supremacy and Britain’s

reluctance to allow Ottoman troops to march through Egypt, reinforcements could

not be directly sent. However, colonels and generals (such as a young Mustafa

Kemal) smuggled their way through Egypt into Libya. Arms were smuggled from

Greece and French Tunisia also. The

influential Sanussi tribesmen of Cyrenaica’s desert rallied armies in support

of the Ottomans, though with poorly armed weaponry.

|

| A young Mustafa Kamel, in Derna (1912) |

In 1912, a

stalemate was reached. The Italians in Tripoli had managed to extend their

radius of control by a few miles, the port of Misrata was captured in February.

Italian troops were deployed to the Tunisian frontier to cease the arms

smuggling. After 11 months, none of the five beach-heads had linked up. The

Italian army dugged in in Derna were besieged by a 10,000-man irregular

army.

|

| The signing of the treaty of Lausanne |

The war was

demoralizing for Italy (who expected it to be a walk-in-the-park) but worse for

the Turks, who faced unrest in the Balkans and other regions.

In July 1912, the

Turks and Italians quietly met in Lausanne on the shores of Lake Geneva. It was

only on 17 October 1912 that both parties declared peace, much to the surprise

of Libyans who felt betrayed. The treaty

they signed was vague; the Ottoman Sultan was to declare Tripolitania and

Cyrenaica as independent and that Libyans were now Italian subjects. In return,

the Italians withdrew from the Dodecanese islands in the Aegean Sea. The Sultan

also retained the power to appoint the grand religious cleric of Tripoli,

allowing the Ottomans to retain religious control over the region.

For the

Italians, it was a cheap and fairly easy victory. The Ottomans could not afford

to continue the war. However, Libyan irregulars continued to fight on. With the

Italians only in control of the coastal settlements, Libya’s interior remained

hostile tribal territory. To the Ottomans, their fight ended. To the Libyans,

their fight has just begun.

References:

- A History of Libya by John Wright, pages 101-114.

- The Making of Modern Libya: State Formation, Colonization, and Resistance by Ali Abdullatif Ahmida, pages 104-105

- Photos from Wikimedia Commons